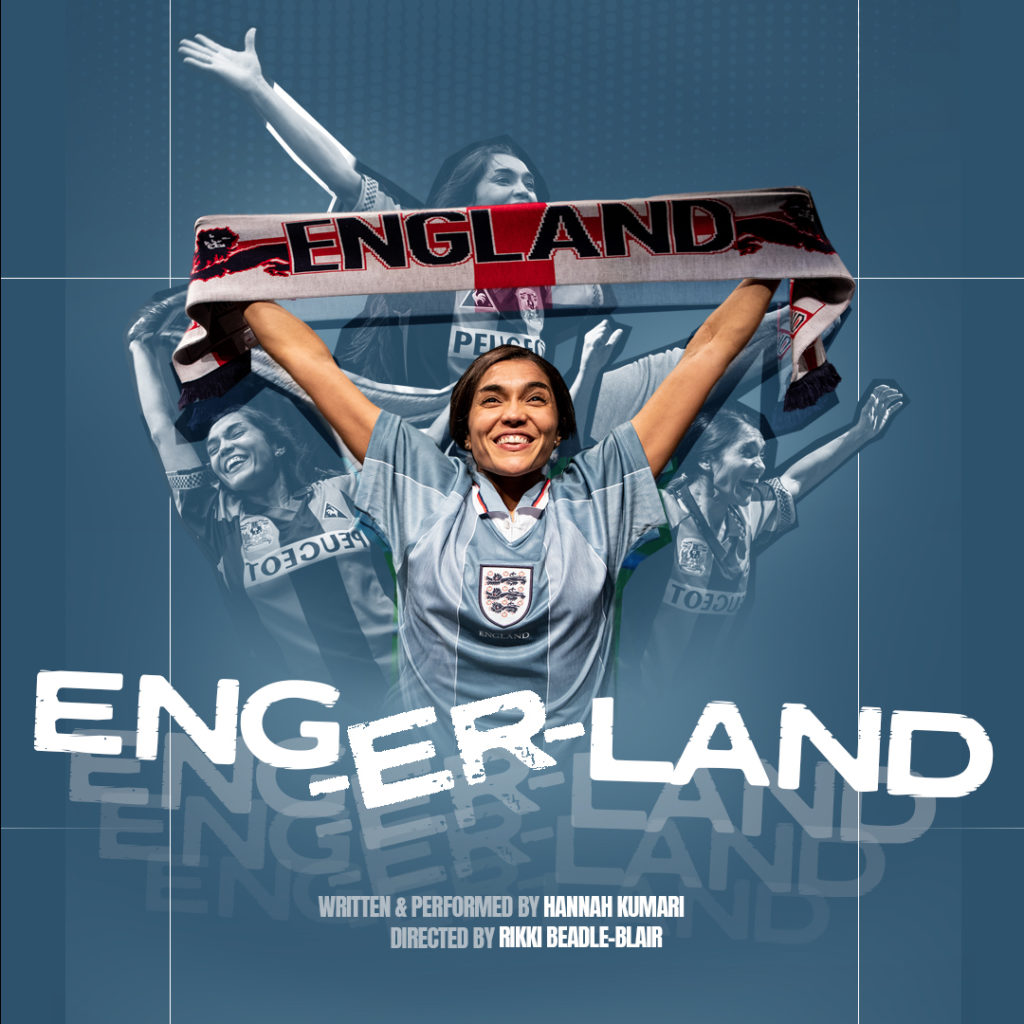

In conversation: ENG-ER-LAND

Published March 1, 2022

ENG-ER LAND – a play about national identity, racism and football fan culture told through the very personal lens of a female mega football fan of South Asian heritage.

Here, Hannah Kumari and former pro footballer Anwar Uddin have put together a blog piece, where you can read all about the play and explore some of the topics surrounding the connection between football and national identity.

ENG-ER-LAND playwright and actor Hannah Kumari In Conversation with Anwar Uddin, former pro footballer, FA Council Member and Campaign Manager for The Football Supporters Association’s (FSA) Fan’s For Diversity, a campaign Uddin set up six years ago which works to promote inclusivity in football.

Anwar Uddin: When you first contacted me with your idea for a play back in June 2020, it was a breath of fresh air – mixing the Arts and football – and just hasn’t been done enough. Your story is so topical regarding the narrative around under-representation, racism and discrimination in football and women’s experiences at matches. It’s also coming from a completely fresh perspective and that’s why I think it will be so well received by the fan base.

Hannah Kumari – I remember you saying to me that football is still quite old-fashioned in terms of getting important messages across – it’s done sitting in a room saying ‘don’t do this, don’t do that’ but as you rightly say, people just don’t respond to that method. So one thing I’ve tried to do with this play is to make it really fun and by writing the story through the lens of a young girl I hope people are more likely to empathise with her.

Anwar – That’s exactly right. I think people will see it as bold and brave. It’s going against the grain of the stuff they usually see. It’s inspired by your personal journey and this is my point, and this is what I’ve tried to highlight through the Fans of Diversity Campaign – it’s time to actually highlight some lived experiences. Use role models like yourself and those from under-represented communities who watch and play football, coaches and referees, and profile and highlight them. I think one of the criticisms I make of my own South Asian community is that I don’t think we do enough to highlight each other, we don’t push each other enough, for many complicated reasons.

My dad used to say to me when he first came over to England many years ago from Bangladesh, that yes, the community did help each other out when they could, but ultimately everyone had their own battle and their own journey to make.

Hannah – Yes, I think it was a form of self-protection.

I’m mixed South Asian and white Scottish and had quite a white English childhood I suppose. For me, writing this play has been a journey of reconnecting with my South Asian heritage, which has been amazing. You talked about your dad coming over here and my ‘Bhabi’ (grandma) came over here from India in 1960. I’ve been thinking a lot about my grandma recently, coming over at that time with two small children. She hadn’t seen her husband for six years, and it’s pretty amazing to think what our parents and grandparents went through.

Anwar – I’m also of mixed heritage and I remember when East is East first came out, over 20 years ago. That film highlighted someone who is very, very Asian who met someone who is very, very white and all the issues that went with that family. My mum is from East London and as Cockney as they come. Her family worked in the markets and pubs, were West Ham fans and as East End as you get. I feel that gave me a massive head start when I was growing up. As a player going into different changing rooms I could sit down with ‘Joe Bloggs’, your average white boy from Roman Road, and talk to him and I felt comfortable. He was like my cousin and on the other hand I could go to a Mosque and to a Muslim wedding and sit with all my Bangladeshi cousins and equally feel at ease. Being able to understand and operate in both cultures was quite rare at the time. I can see why if you are from a predominately Bangladeshi background how you might not understand the football banter, the terminology, the language. Where would you get an opportunity to learn that from? That’s why there is such a disconnect sometimes between the communities. It’s hard.

Hannah – Do you think it puts people off going to football from South Asian communities? Did your dad want you to go to see matches?

Anwar – My dad used to say to me where we were growing up, predominately in the West Ham and Millwall, South and East London areas, that football match days were the worst days. Bricks were going through the windows and there would be non-stop violence. He literally had people chasing him around East London every time him and my mum went out. Racism was ever present. So when I started taking an interest in football and I wanted to go to watch West Ham, he said ‘No, that’s not for us. You can play but don’t watch, that’s for your mum’s side of the family to take you but I wouldn’t’t even feel comfortable with you going with them.’ And that was my experience in a mixed heritage family so you can imagine what your traditional Bangladeshi family would think. You realise and understand why our communities’ relationship with football is via Match of The Day, safe in the comfort of their homes and the teams they supported were Liverpool and Arsenal. That’s why the whole Asian community support those teams.

Hannah – Yeah, yeah, I totally agree.

Anwar – Some people won’t even be aware of that. That’s why I think when you can express your lived experience, for me it’s through interviews and the talks I do, and for you it’s your show, it gives people an opportunity to just think about what it would be like to go to a football match as a Black woman, as an Asian woman or as a young Jewish man. I think that in itself will give the opportunity for fans to empathise and understand the challenges. Because it is a challenge. Sometimes, it is not even the challenge of going to the football match itself, it’s about having the confidence within yourself. For example, when I go and watch an England match away, in Lithuania, Spain or Estonia, I know I have been probably the only non-white face in our whole stand.

Hannah – Even now, that’s crazy isn’t it!

Anwar – And everyone is looking at me. They might not have an issue with me at all, but sometimes I feel a bit uneasy and I ‘m starting to imagine the way people are looking at me. So, my point is sometimes people might not be thinking anything at all but it is something we carry within us.

Hannah – Yes, I definitely identify with what you are saying. If someone is looking at me at a match my default is always to assume it is because of that. Especially when I’m often in places where most people are white and it’s really interesting to think about it like that, it is something we carry around with us.

Anwar – Things are changing though for the better. I do loads of work with clubs all over the country to try and encourage under-represented groups to go and watch football. There is always going to be a minority and the minority are louder than the majority and they always steal the headlines. No one wants to sanitise football but there are some football fans that are holding on to their traditions – watching films like Rise of the Soldier and Green Street – and act like this is their game, and say ‘don’t take it away from us’.

Hannah – That attitude comes from fear doesn’t it?

Anwar – Exactly and to be honest you are never ever going to eradicate that mindset. We are never going to live in a utopia, but someone used the analogy to me the other day about smoking. When the ban was first introduced people said it was never going to be accepted but now if you went into a restaurant and lit a cigarette, firstly you just wouldn’t, but now everyone around you would tell you that you can’t do that. So there’s a critical mass of opinion and everyone has joined in to make it inappropriate and unacceptable.

Hannah – Yeah, was that 2007? It feels like forever now.

Anwar – It is a bit of an extreme analogy but when it comes to racism and other forms of discrimination in football, I think we are slowly getting there because nowadays if someone stands up and says something racist to a Black or Muslim player actually everyone will realise that person is wrong, some will report and challenge it, some may not as it can be quite a scary situation, but I think now we are in a place that people will be saying ‘that is wrong’ whereas 5, 10 or even 15 years ago you would probably have people joining in.

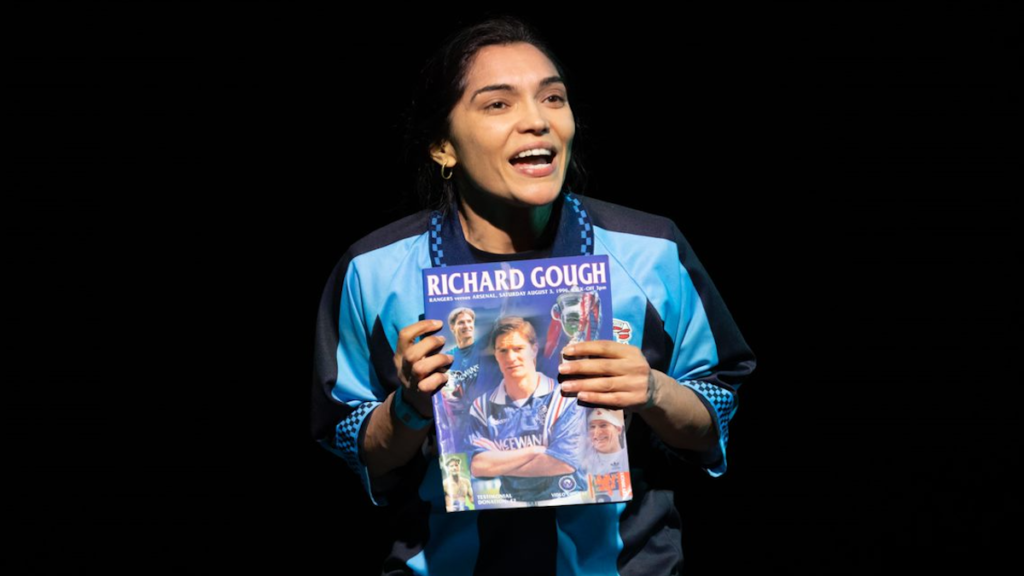

Hannah – Yes, that’s one of the things that I talk about in my play. I don’t want to demonise any particular club but I remember when I was at Rangers in the 90s and hearing a man who was shouting abuse at Ian Wright for the whole game and no one said anything to him. I was standing right next to him and I was about 12 years old and it was really scary. I was a young girl and the only person of colour in that stand hearing that and no one was stopping it. But I think you are right and hopefully it would be different now.

Anwar – There have been times when I’ve been in a stadium as a player and I’ve been subjected to abuse for the whole game because of how bad I was playing and that’s fine and part and parcel of being a player but there is a line you simply don’t cross and that line has been quite a thin line for a long long time. Why is it ok to talk about my skin colour or my religion? I still think there are terms bandied about in the stands which people think are acceptable. For example, I’ve played with Black players where they have been racially abused and the game has been reported but I’ve also played with a friend of mine who is a traveller and heard the whole half of the stadium shouting ‘where is your caravan’, songs and chants that a lot and people think are fine but they’re not. It’s had such a detrimental impact on his confidence and made him a more withdrawn character. I feel like the work I do for the Fans for Diversity Campaign has been my life’s calling because I’ve been having these conversations with myself and living through these experiences my whole life. That’s why I’m so keen to facilitate supporting people like yourself to come and share your story with the fan base.

Hannah – Yeah, I’m so excited to take this show to all these different venues and to football clubs. I did a performance in Bristol as part of a youth festival recently and just seeing the reactions from all different kinds of people about the show has been really fascinating because people take different things from it. I had a guy who was a Bristol City fan and he just loved all of the 90s references. I hope that it will appeal to lots of different people.

Anwar – You are tapping into the nostalgia of everyone’s previous experiences but also reflecting back on your own life as a fan. I think fans across the country are going to really enjoy watching the show and will go home thinking about their own journey but also some of the topics we’ve been discussing.

As a solo performer it must be quite an intense thing to carry a show on your own. There’s no understudy, so you can’t just have an off-night, can you?

Hannah – It is a bit nerve wracking, I’m not going to lie. You are quite exposed when you are performing and no, there’s no understudy, so you’ve just got to push on through.

Anwar – I guess it’s similar to a football player, except we do have substitutes! We are just so proud to be able to support what you are doing. There are so many ways to communicate positive change, new creative ways to show that football is changing and there is still more change to come and I think your show is doing just that!

Hannah Kumari and WoLab present ENG-ER-LAND, coming to Exeter Phoenix on Sat 26 March. Find out more & purchase tickets here >>